HOP articles, stories and insights

From Fatigue to Presence: Mindfulness in Online and Hybrid Learning

Author: Sara Marzo

Illustrations: Freepik, Wikimedia Commons

Licence to (re)use the text of the article: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0

Publication date: January 2026

Introduction

In the fast-changing world we live in, everything evolves quickly—often faster than we can process. Learning is no exception, and in the last decade it has increasingly shifted into digital spaces. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated this trend, showing that online and hybrid learning are not only possible but effective. The growth has been especially strong among young people: Eurostat reports that online learning among young Europeans rose from 29% in 2019 to 46% in 2023. The HOP Research Report on Online and Blended Learning (2023) also shows that those aged 18–25 are the most likely to complete online courses, reflecting their high familiarity with digital learning environments.

This brings incredible opportunities: learning anywhere, anytime, with anyone around the world, at our own pace. Isn't it something unimaginable just a few years ago, finally becoming real—almost like a dream? Still, as with everything, there is also the flip side, the challenges that it takes: long hours at the screen, a stiff body, shallow breathing, constant notifications and that strange feeling of time dissolving. Has it ever happened to you to realise you forgot to drink, stretch, eat or go to the bathroom? Or to look at the clock and discover an hour has disappeared? To feel drained after long hours of screen exposure? This can be called digital fatigue: cognitive overload, emotional exhaustion and physical tension caused by extended time online.

Young people are especially sensitive to this, and youth workers feel it too as they try to hold space and create connection—even through a screen. Mindfulness can help restore presence where the mind becomes overloaded and the body tends to disappear.

Young people are especially sensitive to this, and youth workers feel it too as they try to hold space and create connection—even through a screen. Mindfulness can help restore presence where the mind becomes overloaded and the body tends to disappear.

Digital transformation is also a horizontal priority in Erasmus+, making it increasingly relevant to navigate online environments with awareness.

In this article, we will explore four essential questions:

- What is digital fatigue, and how does online learning affect the body and brain?

- What does mindfulness really mean, and what are its key benefits?

- How can youth workers and learners integrate simple mindfulness elements into online and hybrid learning?

- Which practical tools can support attention, clarity and wellbeing?

This is not an article about becoming “perfect meditators”. It is an invitation to bring embodied presence back into online and hybrid learning—so that learning becomes not only effective, but also humane and nourishing.

Understanding the Key Concepts

Before diving into the realm of mindfulness and its potential gifts in life and learning, let's take a moment to clarify the key concepts that create the theoretical framework we will work within.

Online and hybrid learning. Online learning happens entirely on digital platforms, while hybrid learning combines online and in‑person elements. These formats offer flexibility and accessibility but reduce movement, shared presence and eye contact—signals that naturally support engagement. In youth work, they are now widely used for preparation, meetings, dissemination, mentoring and follow‑up, becoming an integral part of Erasmus+ and ESC practices.

Embodied learning. Learning itself is not only cognitive; it is embodied. Posture, breath, emotions and sensory signals shape our learning experience and influence memory. When learning becomes mostly “head‑based”, especially online, we miss this bodily dimension—and we often pay a physical price for it.

Digital Fatigue. When learning stays online for long periods and remains mostly cognitive, we begin to experience what is known as digital fatigue: a blend of mental overload, emotional tiredness and physical tension.

Digital Fatigue. When learning stays online for long periods and remains mostly cognitive, we begin to experience what is known as digital fatigue: a blend of mental overload, emotional tiredness and physical tension.

The sympathetic nervous system (the one linked to stress) stays activated, long sitting reduces natural movement, the breath becomes shallow, and constant stimuli push the mind between hyper-focus and distraction. Neuroscience shows that this leads to higher cortisol levels (stress hormones), greater cognitive effort and reduced access to the relaxed neural states that support creativity and memory.

In simple words: the brain works harder while the body becomes quieter—an imbalance that affects attention, motivation and overall wellbeing.

What Mindfulness Really Means

Understanding this context helps us see why mindfulness and a more embodied approach are so important. Let’s take one step at a time and clarify what we mean by mindfulness.

If you ask me what mindfulness is, after it entered my life about ten years ago, I would say: It is a philosophy of life, a way of inhabiting the world. Still, I see myself mainly as an evergreen student, practitioner and facilitator, so it feels fair to lean on some recognised voices to define this intriguing – and often overused and misunderstood – word.

Mindfulness is the usual English translation of the Pali word sati, which literally means “memory” or “to remember to observe”. It is an essential aspect of Buddhist practice: a quality of remembering to come back to the present moment.

When many people think of mindfulness, they imagine something religious, or just meditation: sitting cross-legged in silence for hours. Meditation is indeed one of the formal practices of mindfulness, but mindfulness itself is much more than that.

Jon Kabat-Zinn, founder of the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) programme that helped bring these practices into Western medicine and education, describes mindfulness as “paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment, and without judgement.”

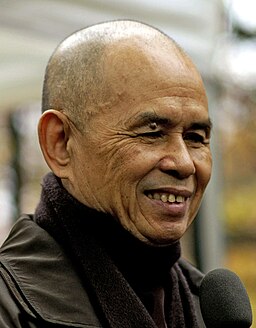

The Vietnamese Buddhist Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh speaks of mindfulness as “touching life deeply in every moment” and calls it “a love story with life.”

From this perspective, it becomes clear that mindfulness goes far beyond a yoga posture or a wellness trend. It is a life-shaping approach: a way of being compassionately awake to what is happening inside and around us, and responding from that awareness.

Mindfulness benefits

Mindfulness has been widely studied for its impact on wellbeing. A major meta-analysis in Clinical Psychology Review (Khoury et al., 2013) shows that mindfulness-based interventions reduce stress, anxiety and depressive symptoms while supporting emotional balance.

Neuroscientific research also indicates that mindfulness lowers stress hormones like cortisol, reduces activity in the brain’s default mode network (linked to mind-wandering) and strengthens pathways involved in attention and emotional regulation.

In simple terms: mindfulness calms the mind, helps us notice thoughts without being carried away, and gently brings us back to the present moment—and to the body.

How Mindfulness Can Support Online and Hybrid Learning in Youth Work

You might still be wondering how mindfulness connects to online and hybrid learning. Let’s begin with a story — a classic Zen story.

Once upon a time, a student visited a master to learn about wisdom. While the student spoke, the master kept pouring tea into his cup until it overflowed. Shocked, the student asked him to stop. The master replied: “Your mind is like this cup. How can I teach you if it is already full?”

Our minds often feel full too — and in online learning they can feel overfilled. Information, tension, expectations, notifications: all of this contributes to what we previously named digital fatigue.

The nature of the mind is to wander. It generates millions of thoughts per day, often drifting into the past or the future — and in digital environments it is constantly pulled by tabs, messages and stimuli. This creates cognitive overload and a growing disconnection from the body, which is our primary anchor to the present moment.

This is where mindfulness becomes a gentle ally. Even a few conscious breaths or a short grounding practice can “empty the cup” and refresh body and mind, creating space for clearer and more effective learning. It is not about doing more or doing better — it is about allowing ourselves to simply be for a moment.

Jon Kabat-Zinn identifies seven attitudes that cultivate mindful awareness: non-judging, patience, beginner’s mind, trust, non-striving, acceptance and letting go. Aren’t these the same qualities that support healthy learning spaces, both offline and online? They help learners approach challenges with more compassion, less criticism and less perfectionism.

In this sense, mindfulness becomes a truly useful ally for our learning journey.

Youth Workers as Space Holders

Before holding space for others, youth workers need space within themselves. Introducing small moments of mindfulness in your daily routine can make your presence calmer and more grounded — and this naturally creates safer and more receptive learning environments. A grounded facilitator models inner clarity. By embodying mindful awareness — observing what happens inside and around you with kindness — you can intentionally bring these qualities into the design and delivery of your online and hybrid programmes.

Practical Ways to Bring Mindfulness into Online and Hybrid Learning

And finally, the practical question: how? How can we bring mindfulness into online and hybrid learning in simple, accessible ways?

Here are a few suggestions from my personal and professional experience.

- Arrival moments: Begin with a short grounding practice: a few deep breaths, a brief guided pause, feeling your feet on the floor, or a small movement to reconnect body and breath.

- Awareness bell: Install a gentle bell on your computer or on your phone that rings every 30–60 minutes. Each time it sounds, stop for a moment, check in with yourself (and your learners), notice your needs, your energy level, the state of your body and mind—and respond with kindness.

- Five senses reset: Invite learners to look away from the screen and reconnect with their senses: notice 5 things you can see, 4 you can hear, 3 you can touch, 2 you can smell, 1 you can taste. Our senses are a doorway back to presence.

- Mindful movement: Create small breaks that encourage standing up, stretching, or taking a few slow steps while breathing consciously. Movement re-awakens attention and helps reset the nervous system.

- Micro-practices between modules: If you are designing a self-paced course, include 1–2 minute pauses between modules to breathe, reset or check in. Make stopping part of the learning rhythm.

- Mindful journaling: Invite learners to reflect on their experience with simple questions:

- How did my body feel during this activity?

- How is my mind right now? What do I need?

- What helped me stay present? What distracted me?

- How do I speak to myself while learning?

- How could I support myself with more kindness next time?

A Broader Perspective: A Shift in Consciousness

As we arrive at the end of this article, we can weave together the threads of what we explored. Moving from digital fatigue to mindful learning requires a shift in perspective—and perhaps even a shift in consciousness.

As we arrive at the end of this article, we can weave together the threads of what we explored. Moving from digital fatigue to mindful learning requires a shift in perspective—and perhaps even a shift in consciousness.

In a world that moves fast, where even learning can feel like a performance, mindfulness invites us to slow down and reconnect. Eco-philosopher Joanna Macy calls this shift The Great Turning: a movement away from speed, separation and overwhelm, toward awareness, care and interdependence.

Mindfulness can be a revolutionary act—an act of care toward ourselves as human beings, youth workers and learners. Each mindful breath is a statement of how we choose to live. How do we want to show up?

I look at the clock: it has been an hour since my last break. I take a breath. My body asks for water. Maybe yours does too.

I wish you presence, gentleness and curiosity as you explore bringing mindfulness into your work and daily life.

And one last piece of good news: here on HOP you can find free online mindfulness courses for youth workers and young people, we created within the Erasmus+ project “You(th) in the Moment”. May they be of service to you.

Author Bio

Sara Marzo is one of the founders of VulcanicaMente APS, a youth worker, mindfulness practitioner, facilitator and ecosomatic coach, with over 13 years of experience in international projects, Erasmus+ and the European Solidarity Corps. She holds a degree in Communication and is completing a Master’s in Neuroscience & Mindfulness, while also collaborating with the Nature Coaching Academy. She is an ICF Italia and ICF Global member and an Associate Certified Coach (ACC).

Her work weaves together mindfulness, ecosomatics, creativity and nature-based methods to support authentic growth, wellbeing and sustainable ways of living. She has created several educational tools, including booklets, e-courses, podcasts and cards, and co-authored Mindfulness and Nature: a Toolkit for Youth Work and Mindfulness for Youth.

References & Further Resources

- Eurostat (2023). Participation in Online Learning.

- Atanasov, D., Kyriakidou O., Molari S., Baclija Knoch, S (2023). Research Report on Online and Blended Learning in European Youth Work. HOP online learning.

- Killingsworth, M., & Gilbert, D. (2010). A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science, 330(6006), 932.

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2013). Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness. Bantam Books.

- Thich Nhat Hanh (1991). The Miracle of Mindfulness: An Introduction to the Practice of Meditation.

- Greater Good Science Center – Mindfulness practices and research.

- Coyote Magazine – Mindfulness for Youth Workers: What's It All About?